R.I.P.: VamoSaviors…

R.I.P.: Transportation Secretary Norman Mineta…

5/6/22—Vamigré mourns the passing of Norman Y. Mineta, 90, who was among so many other things, the first Japanese American to hold US presidential cabinet office. Survivor of a western states internment camp during World War II, Mineta rose to become a 10-term Democratic congressman representing San  Jose and Silicon Valley California, then transportation secretary in the Clinton-to-Bush administrations. He steered civilian air traffic through the 9/11 disaster, and organized the new Transportation Security Administration (TSA) in its aftermath, formed to oversee air-travel safety. Mineta was instrumental in the foundational training of 60k air marshals, and modernizing airport security—as in better screening for weapons, explosives and other contraband prior to boarding commercial aircraft—proceeding to extend such safeguards to ports, rail and bus lines. After overseeing TSA’s migration the new Department of Homeland Security in 2003, he subsequently retired from his secretary role in 2006 after five and one half years. Having served the longest term in the Transportation Department’s 39 year history, he was awarded a Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. Mineta’s hometown San Jose International Airport, also known as a gateway to Silicon Valley, was later renamed in his honor as well.

Jose and Silicon Valley California, then transportation secretary in the Clinton-to-Bush administrations. He steered civilian air traffic through the 9/11 disaster, and organized the new Transportation Security Administration (TSA) in its aftermath, formed to oversee air-travel safety. Mineta was instrumental in the foundational training of 60k air marshals, and modernizing airport security—as in better screening for weapons, explosives and other contraband prior to boarding commercial aircraft—proceeding to extend such safeguards to ports, rail and bus lines. After overseeing TSA’s migration the new Department of Homeland Security in 2003, he subsequently retired from his secretary role in 2006 after five and one half years. Having served the longest term in the Transportation Department’s 39 year history, he was awarded a Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. Mineta’s hometown San Jose International Airport, also known as a gateway to Silicon Valley, was later renamed in his honor as well. ![]()

R.I.P.: The VamoSavior of Sioux City…

9/2/21—Before the ‘Miracle On the Hudson’, there was the Crucible of Sioux City, Iowa.

To recall, Captain Chesley Sullenberger safely landed Flight 1549, his stricken A320, on New York’s Hudson River in 2009, saving all aboard. “Sully” has been an international hero, celebrity and aviation consultant ever since.

Well, some 20 years earlier, a United Airlines DC-10 took off from Denver, Colorado bound for Chicago, Illinois. Barely one hour into the flight, however, a defective, fatigued fan disc broke apart  (as had many other such titanium discs) in Flight 232’s tail-mounted #2 GE CF6-6 engine. An immediate bomb-like explosion destroyed the tri-jet’s hydraulic cables, which effectively cut the cockpit off from the length of the airframe, to where the crew could no longer steer the plane nor control its speed.

(as had many other such titanium discs) in Flight 232’s tail-mounted #2 GE CF6-6 engine. An immediate bomb-like explosion destroyed the tri-jet’s hydraulic cables, which effectively cut the cockpit off from the length of the airframe, to where the crew could no longer steer the plane nor control its speed.

The McDonnell-Douglas DC-10, already a suspect aircraft safety-wise* began to turn to the right, starting to roll—threatening to flip upside down, to the horror of all 296 on board. The plane’s vital hydraulic fluid pressure was plunging to zero level, and the jumbo jet reached 38° of bank. Its two remaining engines could not be throttled back, much less shut down, and the right-rolling aircraft was losing altitude fast.

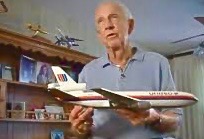

Panic was in the air, all right, but not in Flight 232’s cockpit. Captain Alfred Clair Haynes (above) had commanded the yoke from his left seat, instinctively attempting to slam the #1 engine, throttle the #3. His DC-10 was theoretically designed to fly on just its two wing-mounted engines when necessary. But in this case, he and his crew couldn’t (rudder) yaw, move elevators and ailerons to curb banking into a curve; had no horizontal stabilizer, flaps or slats with which to slow the jet. All the flawed plane’s hydraulic lines were located in one (single point-of-failure) vulnerable location. So the crew had lost all hydraulic control of the plane; and if it bellied up, Flight 232 was sunk.

Everything else having failed, Haynes was able, through sheer savvy airmanship, to steer the crippled jetliner via ‘asymmetric thrust’, by jockeying its wing-mounted engines, left and right to better level the aircraft, despite only being able to turn to starboard.

Same time, flight engineer Dudley Dvorak manned the gauges and dials from his jump seat while First Officer William Roy Records radioed “November 1819 Uniform (a/c # N1819U) calls emergency to Sioux Gateway Airport control tower,” following direction from the Minneapolis Air Route Traffic Control Center to the nearest runways for a DC-10 landing.

VOR contact made with the tower and FAA, Haynes and his crew coaxed the wounded jetliner for nearly an hour, jiggering throttles in dizzying 5-10 mile spirals, product of virtually uncontrollable right turns. This was unheard-of, seat-of-the-pants maneuvering, according to tower controllers and other monitoring aviation authorities.

Alert two status: “On Sioux City approach, United Two Thirty-Two heavy.” Haynes wrestled the lurching aircraft into a southbound one-eighty heading, wind at its back, the airframe ‘porpoising’ hundreds of feet every minute, wafting like a burger wrapper in a gale storm. His cockpit team steered the DC-10 by tweaking the speeds of the two remaining engines while struggling against its undulating movements.

Inspired, innovative airmanship, to be sure. Still, they were sinking 1,800 feet per second as the craft approached Sioux Gateway’s emergency runways too steeply and far too fast at 250 mph—still carrying 37,600 lbs. of jet fuel—everything a blur. “Brace, brace, brace!”: Touching  down, the plane’s right wing dipped from a 2° to 20° bank, ripping into runway 22. Flight 232 bounced and cartwheeled up on its nose, the tail section totally breaking away, seat rows tearing free, tumbling onto the runway—many with passengers still strapped in place.

down, the plane’s right wing dipped from a 2° to 20° bank, ripping into runway 22. Flight 232 bounced and cartwheeled up on its nose, the tail section totally breaking away, seat rows tearing free, tumbling onto the runway—many with passengers still strapped in place.

Shuddering and wrenching, the entire plane fractured in a fuel-fed fireball of smoke and hellish flames, engines shearing off, a huge rush of dirt, grit and shattered glass. Having scorched and scarred a long, frightful, skid-marked trail along runway 22, what remained of the jet’s fiery fuselage settled upside down in a bordering cornfield, dozens of dead still trapped inside. Around them, ejected passengers, the main cabin, tail section, cockpit, engines and landing gear were strewn everywhere.

It was United’s worst crash since a Flight 811 Honolulu-Auckland 747 with 337 passengers and crew of 18 blew off a cargo door on February 24, 1989, explosive decompression tearing a huge hole in the passenger compartment, which sucked out nine passengers before the jetliner could return to Honolulu’s airport.*

Yet here in Iowa, Haynes and crew’s extraordinary piloting under life or death duress saved the lives of over 180 of the 296 aboard. And although the captain long suffered survivor’s guilt for not sparing the lives of all of his ill-fated Flight 232 passengers, he recently passed away in Tacoma, Washington, age 87, a true aviation hero in the “Sully” Sullenberger sense.

Not to mention a genuinely legendary VamoSavior watching over us fellow travelers from his first chair in the sky. A world of thanks, Captain Haynes, and to your entire valorous crew…

![]()

*Prior to that, American Airlines Flight 191 crashed upon takeoff from Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport on May 25, 1979, when its left engine broke away from the wing due to a carelessly maintained pylon: The NTSB said at the time that it was a ‘crowd killer’ of 273 passengers and crew, the worst commercial airplane accident in U.S. aviation history. A Lockheed L-1011 Tri-Star with a similar tail-mounted engine design, Delta Flight 191 crashed on August 2, 1985 in a severe Grapevine, Texas microburst, killing 123. The Tri-Stars never proved to be much safer than DC-10s before they too bit the dust in some Arizona desert ‘aero graveyard’.

Airport on May 25, 1979, when its left engine broke away from the wing due to a carelessly maintained pylon: The NTSB said at the time that it was a ‘crowd killer’ of 273 passengers and crew, the worst commercial airplane accident in U.S. aviation history. A Lockheed L-1011 Tri-Star with a similar tail-mounted engine design, Delta Flight 191 crashed on August 2, 1985 in a severe Grapevine, Texas microburst, killing 123. The Tri-Stars never proved to be much safer than DC-10s before they too bit the dust in some Arizona desert ‘aero graveyard’.![]()