737-8: The MAX Factors.

Boeing 737: Hitting MAX 2 (Premise).

Victims are being identified, black boxes decoded and the world’s fastest-selling airliner is currently remaindered on the ground. It could be months before the Boeing 737 MAX 8 is re-certified as airworthy, even longer before we, the traveling public will confidently board those planes again. So what are the Vamifications of all this tragic misadventure, what are the VamoScenarios flying forward?

Good a time as any to scan the Ethiopian Air contrails, and vector the disaster’s afterburners—factor by factor, sector by sector, interest by interest—fairly coursing thru the clouds:

Playing FAAvorites.

The question is not how the Federal Aviation Administration could have dragged it tail on the MAX 8 grounding, but why?

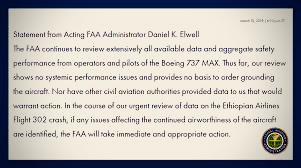

Risk analysis, data-driven, no systemic performance issues, no data to warrant action, no justification to order grounding the aircraft’—continued airworthiness notification—’the agency will take immediate and appropriate action’ if it ‘identifies any continued airworthiness issues on the MAX…

This was the stream of unconscionable statements coming from the FAA, issued primarily by acting Chairman, Daniel Elwell as the world closed ranks above and beyond the agency to ground MAX 8s for proactive reasons of safety and surety. A chairman in an acting role for well over a year; nothing  permanent—it was either him or President Trump’s private pilot with Department of Transportation Secretary (and Elwell ally), Elaine Chao dutifully rubber stamping along the way.

permanent—it was either him or President Trump’s private pilot with Department of Transportation Secretary (and Elwell ally), Elaine Chao dutifully rubber stamping along the way.

Curiously, Elwell’s stall was only circumvented by Trump’s abrupt change of direction (this, after his earlier futzing around with the process) in the face of public and mainstream and social media outrage. Further data on vertical speed, plus physical and refined satellite evidence from the crash site reinforced the urgency of the FAA’s belated grounding order, based on a ‘common thread’ of Ethiopian Air ET 302′s ‘clear similarities’ with Lion Air’s JT610 disaster. The agency responds only that its aircraft certification processes are well established, replied Elwell, and have steadily produced safe aircraft designs.

Still, as to best practices, why the tail dragging, all the ‘patience and prudence’ until the data ‘fully coalesced’? Aviation industry critics say look to the bottom line.

Since its inception in 1926 under the Air Commerce Act, the FAA has perhaps never been as financially strapped as it is today. Short on funding and staffing, the agency is under further fiscal pressure, with Trump recently vowing to cut some $400m more from its $17.5b annual budget.

This combination of resource trimming and lack of permanent, dedicated leadership has fundamentally weakened the agency’s oversight and safeguarding of the nation’s $850b aviation system. As a result, some questionable ‘standards and practices’ have crept into its agency’s regulatory responsibilities. From the beginning, the FAA has seen its mission as a cooperative partnership with the growing aviation industry—simultaneously policing and promotional in nature—a dual role that lasted until the ValuJet crash in 1996, wafting into a 2008 Southwest Airlines inspection scandal, and was ‘officially’ jettisoned by 2009.

DelegateGate? Hands On/Hands Off.

Yet since then, that coziness had quietly persisted—e.g., airlines as clients/customers—but no more so than with the Boeing Corporation, particularly when it comes to airworthiness certification (as detailed below). The agency’s eroding authority has been increasingly evident through these recent MAX 8 crashes, to where former NTSB head, James Hall has called for a Congressional investigation, what with passenger safety at unacceptable risk—which the House and Senate now intend on conducting, along with the D.O.T..

Chairman Hall cites adverse agency dependence on Washington D.C.’s ‘money system’, and a 2005 shift in FAA regulatory oversight, wherein the agency began delegating significant safety/airworthiness certification to the industry itself. This ‘modern oversight’ allowed a thousand or so ‘qualified designee’ Boeing engineers to conduct  self-certification of its new aircraft off the assembly line, due to ‘limited FAA resources and lack of suitable inspection personnel’— internal company cross pressures and conflicted interest, or no.

self-certification of its new aircraft off the assembly line, due to ‘limited FAA resources and lack of suitable inspection personnel’— internal company cross pressures and conflicted interest, or no.

Boeing’s Designated Engineering Representatives have been coordinating safety certification in-house since the 1970s-80s—a delegation program that actually dates back to the 1920s—with the FAA reviewing their findings for final approval. Boeing designees began assuming more and more of this ‘hand-off’ under an Organization Designation Authorization (ODA) in ’05, however, what with the agency once again lacking resources to oversee every part of every plane.

But by 2016, the company had pressed its legion certification engineers to ‘dial back’ testing a fire suppression system for its jets’ big new LEAP engines, allegedly removing one senior engineer who had pressed for more stringent testing. Gradually Boeing managers pressured more of its ‘authorized representatives’ (AR), employed to be the FAA’s ‘eyes & ears’, to rein in safety analysis and testing so as to meet the company’s accelerating production schedule and keep costs down.

For its part, the aviation agency leaned on its own inspectors to let Boeing provide greater direct onsite oversight. FAA technical staffers increasingly rubber-stamped the AR reports to expedite safety assessments and certification, while providing the ARs little or no protection from potentially chilling Boeing management coercion.

This outsourcing ‘team scheme’ strays alarmingly from the FAA’s mandate of rigorous oversight, says Hall, and leads to declining public confidence in air travel, if the agency fails to retain independent investigators who will ensure the highest level of airworthiness certification. Otherwise, the agency will be seen as a tombstone agency, outsourcing analysis, no longer grounding unsafe aircraft until evidence or pressure leaves it no other choice. Thus forfeiting its long leadership role in the world’s air safety ecosystem, the FAA will ultimately be bumped like a standby to the rear of the global safety line.

So no surprise that the U.S. Justice Department’s criminal (fraud) division and Department of Transportation inspector general’s office are now looking into this FAA-Boeing self-certification program, and the entire developmental process of the 737 MAX 8 aircraft. Verdict so far: Too sold out, too slow at the yoke, but the agency’s chances of getting any better under this administration—even as it vows to run a slower, surer certification process from here on? Not many when it’s up against a political ‘wall’…

The Flawed Couple.

MAX 8/9: Boeing, going, gone (wrong)? For want of diverging vertical speed graph lines and a rightly positioned jackscrew. But it wasn’t meant to be…

A frantic phone call to the Oval Office by Dennis Muilenburg, confidently reassuring the president as to the MAX 8’s safety and reliability, beseeching Trump to keep the planes flying through the downer atmospheric pressure. The CEO’s plea was soon followed up with his deflated callback to finally ground them. Trump then declared, ‘Boeing is an incredible country, but safety is paramount!’ well after the fact.

First, however, a bit of backstory on the MAX 8 Boeing aircraft now in question: In retrospect, seems its glorious conception and timely birth was more of a preemie ceserean rollout.

Cruising atop the commercial aviation hierarchy in 2010, the 737 line was already Boeing’s cash cow, had been its best-selling single aisle model since launching in 1967. Then came the Airbus A320neo.

Cruising atop the commercial aviation hierarchy in 2010, the 737 line was already Boeing’s cash cow, had been its best-selling single aisle model since launching in 1967. Then came the Airbus A320neo.

Somewhat technologically sleeker, 20% more fuel efficient, the new Airbus SE entry in 2010 suddenly created turbulence in the small, single-aisle market sector. Feeling the competitive heat, Boeing scrambled to develop its own rangier, more fuel efficient entry—nine months behind, the Airbus Neo beginning to take Boeing’s lunch with major customers such as American Airlines—playing catch-up, and fast.

No time to hit a clean, white drawing board, the manufacturer decided to go with what it had. So continuity and similarity were the headings as Boeing sought to beef up and fuel down its nearly half-century-old mainstay. Simply enlarge the engines on the ‘world’s largest selling commercial airplane’, design in greater fuel efficiency, update its analog-to-digital computer technology—particularly to compensate for the bigger engines. Then the company rapidly rolled out its reworked ‘old-school’ workhorse within months, the 737 already veteran of a dozen variants, instead taking the time and trouble of building a totally modern aircraft from scratch—a shortcut just in time, at that.

Boeing immediately pitched the 737 MAX as an advanced, fuel-efficient money saver (lower price tag, 14% less fuel thirsty; 8% leaner operating costs) hewing faithfully to the ‘Baby Boeing’ 737s already in airline fleets, thereby requiring minimal added maintenance chops or pilot training. The FAA promptly certified the plane in 2017, and airlines had bought in instantly with preorders in 2011, making the MAX Boeing’s fastest selling model ever. Carriers worldwide have since taken delivery of over 350 units, placing orders for 4,600 more.

Another MAX selling point was its sophisticated, advanced ‘fly-by-wire’ operating system to aid and  increase flight crew ease and performance: Max efficiency, max safety, max passenger appeal. The key was software to account and correct for any untoward flight conditions and/or irregularities (e.g., the larger engines’ propensity to generate more lift)—similarity and simplicity coded in so that costly simulator pilot training on the MCAS automated system would not be necessary. Instead, a flight/maintenance manual update would suffice.

increase flight crew ease and performance: Max efficiency, max safety, max passenger appeal. The key was software to account and correct for any untoward flight conditions and/or irregularities (e.g., the larger engines’ propensity to generate more lift)—similarity and simplicity coded in so that costly simulator pilot training on the MCAS automated system would not be necessary. Instead, a flight/maintenance manual update would suffice.

Problem was, neither Boeing nor the FAA thoroughly alerted airline customers and their crew to MCAS attributes, tolerances and tendencies. Apparently, the consensus was, pilots didn’t need to be explicitly trained or even told about the new anti-stall system, that they would quickly recognize a runaway horizontal stabilizer and hit their corresponding cutoff switches.

Still, airlines the world over flocked to the MAX 8, pilots and passengers loved it, and Boeing basked in the afterglow of so speedily and successfully addressing the demands of a changing air travel landscape. Skies were clear and blue, save for that 787 Dreamliner hiccup over its lithium battery fires, a grounding that was short and bittersweet, yet successfully resolved with a new fireproof casing posthaste.

Manhandling Defects or Massaging Data?

Otherwise, thanks to its healthy balance sheets, the company had been incorporating further technological advancements into its entire design and production process—automation and outsourcing reigned supreme. Boeing management recently introduced ‘smart tools’ like digital wrenches that will eliminate thousands of quality checks for defects and 450 inspectors each this year and next. This ‘quality transformation’, derived from automobile manufacturing, will make design and building ‘just right the first time’—ergo streamlined production wherein the responsibility for inspection ‘goes to the mechanic’.

The FAA is monitoring and supporting Boeing’s ‘transformation’, maintaining that inspection requirements aren’t changing, only the methods—while ostensibly auditing the new Process Monitoring system. But many current inspectors question the program’s capacity to detect poor workmanship and defects, or if they are being data documented at all.

Meanwhile the company’s unions aren’t buying ‘quality transformation’ whatsoever, International Association of Machinists workers decrying job elimination, as well as production line pressures as plane output targets increase by the score. Under IAM’s banner of ‘It’s not OK to cut QA’ (Quality Assurance), the union charges Boeing will be masking defects, schedule-driven newbie engineers overriding QI defect reports artificially massaging data, rather than seasoned inspectors physically examining the planes.

In all, it’s been making for assembly line complacency and sinking morale on the shop floor, not least among the 10,000 workers in Boeing’s Renton, Washington 737 plant. Soon there surfaced a number (4) of whistleblower complaints on the MAX program.

Then came news of the Ethiopian Air crash, on the heels of last year’s Lion Air MAX 8 disaster…

A Tail of Two Pities.

As we all await the latest black box data downloads, more and more disturbing elements come to light. Soon after the Ethiopian Air crash, for example, the plane’s vertical speed graph line eerily paralleled that of Lion Air’s JT610, both similarly oscillating up and down virtually upon takeoff, unreliable airspeed and altitude readings, triggering the stick shaker as well. In both cases, pilots frantically flipped through Boeing technical manuals to ferret out a source of and remedy to their rollercoaster ride, to no avail.

Then the aircraft’s tail section jackscrew was recovered by site recovery crews, significantly out of normal operating position, possibly indicating extreme upward pressure on its horizontal stabilizer. By that time, the  MAX 8 grounding order was universally in place, investigations proceeding from Addis Ababa to Seattle.

MAX 8 grounding order was universally in place, investigations proceeding from Addis Ababa to Seattle.

Questions abounded, similarities between the two air disasters too close to ignore or easily explain away. These were popular state-of-the-art airplanes that had met all FAA certification and regulatory requirements (including its MCAS flight control system) since rolling out of Boeing’s Renton plant in late 2015. They were being ordered by the thousands by airlines the world over.

Thus the dig went deeper, all the way back to the MAX 8’s beginnings in 2011. How Boeing had been playing catch-up to Airbus’s A320neo, that FAA managers and engineers were pushed to meet the new 737 variant’s tight certification dates. That Max’s unique selling proposition was minimal training and ease of use thanks to its ‘commonality’ with the 737 line. So what was with that Ethiopian ET 302 jackscrew-up?

Who’s Flying This Bird?

Turns out a 2015 FAA safety analysis understated the MAX operating system’s power to trigger the plane’s stick shaker and maneuver its horizontal stabilizers on the tail, that jackscrew for which was set four times farther than specced in the initial documentation. Boeing originally ascribed a tail movement maximum of 0.6 degrees (out of just under 5 degree scale). But after the Lion Air JT 610 crash, Boeing quietly restated the limit up to 2.5 degrees, which would have allowed for greater upward tilt of the horizontal stabilizer (which ‘trims’ the plane) to full stop, thereby pushing the its nose down with unlimited authority. Moreover, the activated MCAS software would repeatedly reset that stabilizer, jacking it down in further increments each time a pilot tried to manually override the system.

Wait, airline pilots would know all about that, right—it went without training. Not according to the Airline Pilots Association, which notes that MAX 8 ‘training’ basically consisted of a nearly one-hour session on an I-Pad, no time/money for ‘unnecessary’ simulator instruction, as it were. And that was for mainly U.S. flight crews, no telling how the MCAS heads-up bulletin was afforded to pilots overseas. In fact, Ethiopian officials claim that a highly regarded pilot for Africa’s foremost carrier likely had little or no such training on its simulator whatsoever, much less the cockpit crew on budget-strapped Lion Air.

Tackling A Tailspin.

Boeing says these and other safety issues are currently being addressed in its MCAS software upgrade,  finally due out in April, per the latest FAA airworthiness directive. Improvements will include a one-cycle (only) ‘kick in’ swivel of the MAX 8’s horizontal stabilizer. Plus the addition of a second active angle-of-attack vane on the nosecone, with AofA readings indicators, and ‘disagree’ lights to signal when the two AofA sensors, which trigger MCAS in the first place (by measuring the difference between the pitch the plane and direction it’s moving through the air), are out of accord. These will no longer be costly (ergo, highly profitable) tack-on options. For it likely was the MAX’s lone sensor that represented Lion Air’s single point of failure, with a 20-degree variance between the two vanes throughout the JT 610 flight.

finally due out in April, per the latest FAA airworthiness directive. Improvements will include a one-cycle (only) ‘kick in’ swivel of the MAX 8’s horizontal stabilizer. Plus the addition of a second active angle-of-attack vane on the nosecone, with AofA readings indicators, and ‘disagree’ lights to signal when the two AofA sensors, which trigger MCAS in the first place (by measuring the difference between the pitch the plane and direction it’s moving through the air), are out of accord. These will no longer be costly (ergo, highly profitable) tack-on options. For it likely was the MAX’s lone sensor that represented Lion Air’s single point of failure, with a 20-degree variance between the two vanes throughout the JT 610 flight.

Now whether the Ethiopian Air’s black box data dump or Boeing’s much anticipated software fix are too little, too late remains to be seen.

One interesting sign is the appointment of a new, permanent head of the FAA, former Delta Airlines senior official, Stephen Dickson, who will presumably be charged with ‘putting safety ahead of airline profits’ once again, returning the agency to the ‘gold standard’ of aviation safety—pending Senate confirmation, that is. This development, Vamigré will track with satellite precision—to see if Elwell’s, that ends well.

Clipped Wings.

As for Boeing, the manufacturer has some heavy headwinds to navigate, to be sure.

A somewhat chastened CEO Dennis Muilenburg recently took to full-page major newspaper ads, speaking to the bruising his company has been taking, from the cockpit to the tail.

His PR mea culpa and commitment to quality and safety notwithstanding, a one-two punch of erratic, wobbly takeoffs and chilling, near vertical 300-400 mph nosedives has landed Boeing in a D.O.T. probe—even Justice Department possibly criminal investigation. European and Canadian aviation authorities decide to conduct their independent airworthiness certifications going forward.

Pilots and flight attendants unions are furious over the MCAS no-know, contending breach of trust. Carriers such as Garuda and Norwegian Air threaten to cancel orders and take their business elsewhere, and no amount of D.C. Juice will easily mitigate all that.

Boeing’s leaner manufacturing program, its Detroit-Style assembly line automation/tech push now faces reality turbulence, is learning the painful lesson, that aircraft ‘hiccups’ mean not mere airbag recalls, but airborne baggage and bodies strewn by the planeload.

Tolling the Bads for Boeing.

While Ethiopian Air’s black boxes spill more crash data, April brings an MCAS software fix, and a testy MAX recertification process plays out, Boing assesses the overall damage from delayed deliveries and lost revenue compensation (running in the $millions) and corrects course amid the biggest crisis it has faced in decades.

During this 370-plane grounding, the FAA is allowing the company to fly/ferry its empty 737 MAX 8/9s around to King County Airport tarmacs and eastern Washington (Moses Lake) facilities for purposes of  parking and storage. Boeing will continue to produce and stack its ‘greenie’ planes, but not deliver them to its airline and (wet) leasing group customers in the interim—white tails or otherwise.

parking and storage. Boeing will continue to produce and stack its ‘greenie’ planes, but not deliver them to its airline and (wet) leasing group customers in the interim—white tails or otherwise.

No cost-free decision here, as the manufacturer will continue to keep some 52-57 model 737s rolling out Renton’s doors per month. For no matter how they and a chorus of industry analysts claim that this grounding/impasse amounts to nominal chump change given the aerospace giant’s $100b annual revenue, Boeing could now use the projected income stream from this bread and butter product line: At $300m per MAX plane they are nearly 70% of future delivers, 40% of the company’s profit.

Meanwhile, its share price has dropped between 5.3% and 13% since the Ethiopian ET 302 disaster, peeling upwards of 11% off its market cap during a resulting Wall Street retreat. Moreover, a lengthy software fix process could ultimately cost $5.1b, or 5% of annual 2019 revenue (29% of the total). Thus good thing building airplanes is what they are so committed to doing.

Hightailing it: Righting the Airship.

Otherwise, in the wake of ‘DelegateGate’, Boeing’s primary task is to restore the safe/sure trust of the public and industry alike, secondarily rehabbing its reputation.

Whatever the case, here is a 100+ year-old company—one of a duopoly even up to designing and building these complex aerodynamic transport machines, these flying miracles, at least until China’s Comac C919 catches up. Fact is, there are contract penalty stipulations and airline cash advances Boeing holds that could be subject to forfeiture. Further, Airbus SE is already backlogged (three-year wait time, even at a 60-per-month pace), and can only ramp up A320neo production so much more—single-aisle skies being limited on that route.

So as corporate/mainstream media move on, Vamigre will be watching closely for the 737 MAX 8/9s’  inevitable return to airline fleets worldwide, Boeing fulfilling its seven-year, 4,600 order backlog—with a new vow to ‘make an already safe aircraft even safer’.

inevitable return to airline fleets worldwide, Boeing fulfilling its seven-year, 4,600 order backlog—with a new vow to ‘make an already safe aircraft even safer’.

Roger that, just so long as it isn’t an ElectraFlying experience all over again…

Carrier Wait and/or Flee.

But until Boeing does so, airlines find themselves wrestling with the 737 MAX 8’s grounding and its repercussions, scrambling to adjust immediate daily schedules, assessing the bottom-line damage while calculating claims to the plane builder for disruption related compensation.

True, some airlines did fly in formation with the plane maker when news of Ethiopian Air ET 302 catastrophe first hit. American, United and Southwest Air continue to operate their MAX 8s as carriers worldwide grounded theirs, maintaining that initial facts and evidence didn’t warrant pulling them from the skies—right in lockstep with Boeing and the FAA. That is, ‘prudently’ coursing a fine line between customer service and aviation safety through a data driven storm.

But winds did shift fast and furiously, with the Oval Office rendered a decisive gust/blow: Down came  MAX 8/9s, over 370 globally, until their MCAS/control law issues are safely resolved.

MAX 8/9s, over 370 globally, until their MCAS/control law issues are safely resolved.

Since the full force grounding, domestic U.S. carriers’ initial confidence has yielded to managing chaos: Cancelling flights, substituting/leasing other planes, shuffling schedules, moving their remaining fleets around from airport to airport to meet wary, disgruntled passenger demand.

Southwest Air, with its fleet of 34 MAX jets (+ 42 more due them this year), is being hit particularly hard, with burgeoning cancellations and revenue cuts—against rising fuel and ‘enhanced’ storage costs.

Such is the disruption, at least until 737 MAXs are fixed, re-certified and are safely airborne again. Some carriers aren’t keen on waiting, however, and are planning alternate routes in the face of some bracing financial headwinds.

Garuda Indonesia, for instance, has announced the cancelling of its MAX jet order, customers having lost confidence in the Boeing aircraft. Canada’s budget WestJet and Vietnam’s VietJet are not far behind.

Norwegian Air is especially feeling the MAXless pinch, having 18 MAX 8s (in a fleet of 160 planes), with another 92 on order. So it intends to bill Boeing Corporation for the operational costs and mayhem. Air Canada numbers 24 MAXs in its fleet, but has recently changed its pending Boeing order to Airbus SE 320neos.

Clearly, the grounding’s duration will determine whether a carriers’ spinoff or withholding pattern spreads further across the airline skyscape.

Now, question is, what do the Boeing 737 MAX 8 failures, fallout and remedial fixes mean to Vamigré travelers like us? (MTC)…

<< 737 MAX: The Fix Is In?

<<< Accident Update: Lion In Wait.